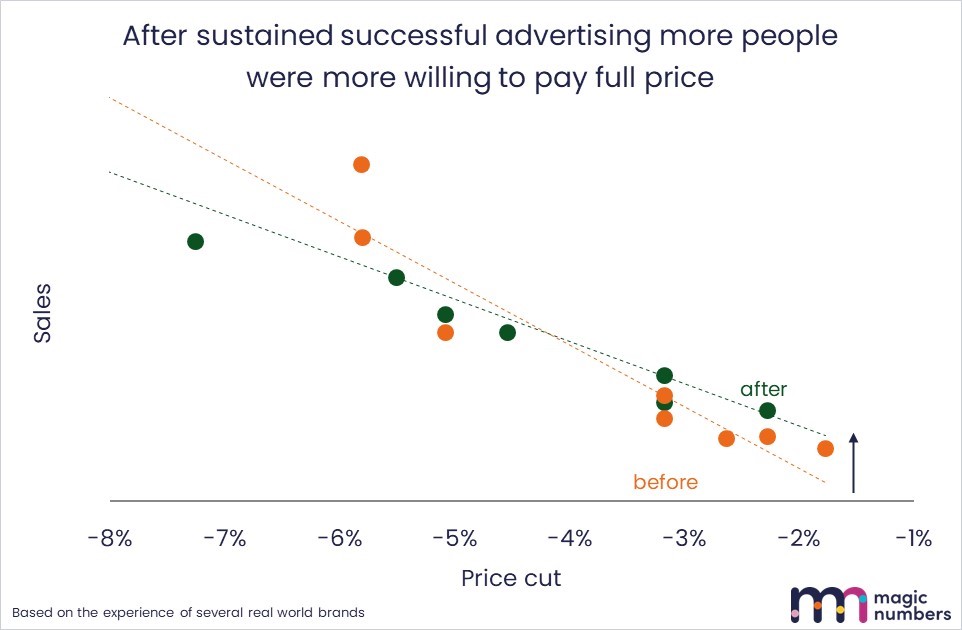

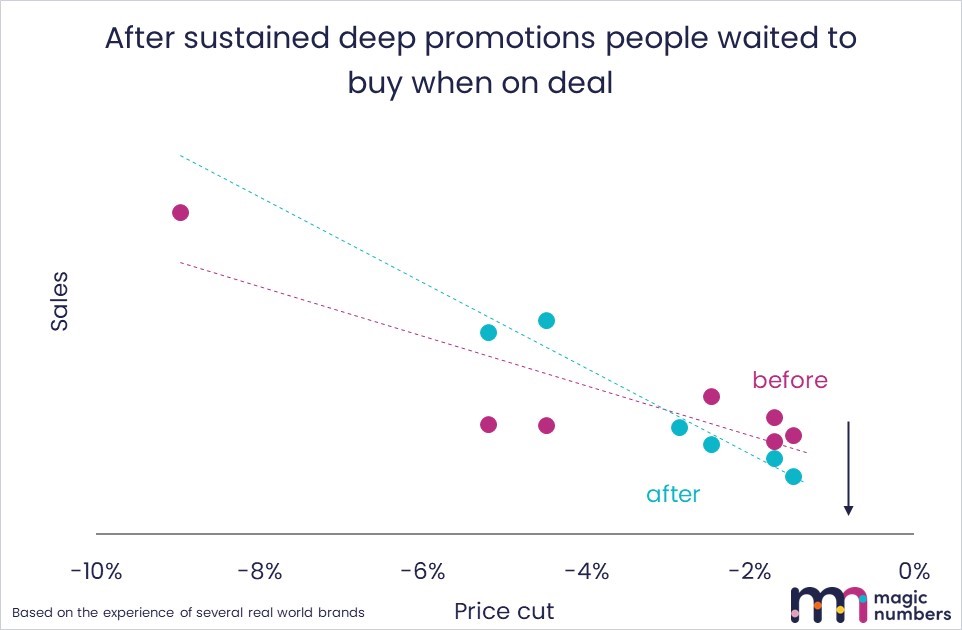

It’s true. Willingness to pay a high price is something that marketers can change.

The evidence shows that if you consistently air good quality advertising and invest in your brand, you build up associations that mean people buy it just because it’s easy to think of, or out of habit. Some will buy it without checking the price, others might check prices but still decide the product is worth paying more for.

It’s not an easy win. Even with great creative and a good budget, willingness to pay might only change to some extent, and only with some people. Even so, the money magnitudes involved mean that this effect may well be the biggest business benefit of advertising.

And right now, as the cost of ingredients, components, and especially energy is increasing rapidly, many businesses are being forced to increase prices. Willingness to pay and how to bolster it should be at the forefront of marketers’ thinking.

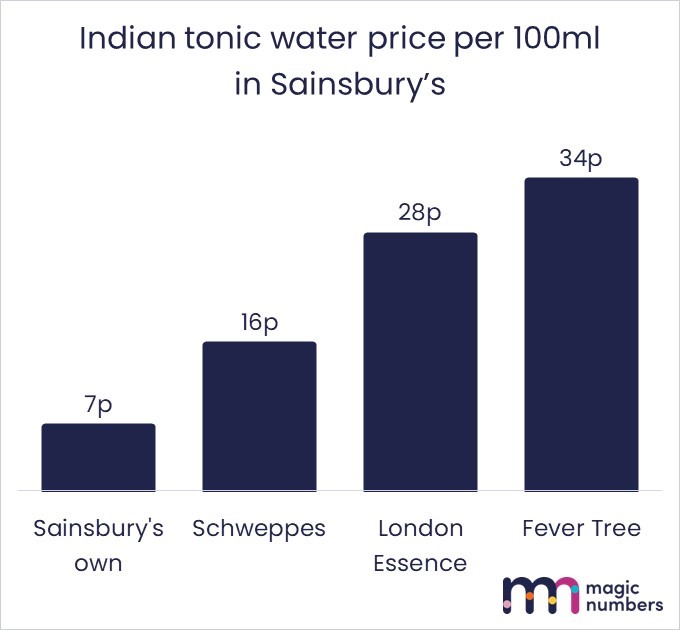

Branded products sell for more even if they are the same or worse quality

The simplest and clearest evidence that marketing affects willingness to pay is on display on supermarket shelves and comparison websites everywhere. Own label products which aren’t specifically marketed sell for less than those that are.