For the first time this Autumn, a number of marketers that work on big brands and think about strategy and positioning, emotion and nuance have had a look at search data. Previously it had mainly been used by that other type of marketer. The type that chooses keywords, buys search ads, and optimises websites for SEO.

And guess what? The big brand, big budget marketers have found it very exciting. Because – as Les Binet and James Hankins have shown – share of search is related to share of voice, and sometimes it can even predict market share.

That’s interesting, but it only scratches the surface of what there is to learn from search data. When people search, they type in what they want or need, and often, what they’re willing to pay for. The data that those searches generate builds to nothing less than a full and detailed description of what economists call demand, or in other words, what it’s possible to sell.

This means that search data is a gold mine for marketing strategy. It reveals which types of product are most in demand and which aspects of them are most important to consumers. It can inform on how to position a brand for growth and even what words and tone will work best in creative executions.

Search often does a different job to other channels

This is not to say that pulling google trends for your brand name and that of your most important competitors to see who’s getting the most searches – as Binet and Hankins propose – isn’t useful. It quite clearly is.

Share of search gives a quick read on how in demand your brand is versus theirs, and that’s a handy yardstick for how well you’re doing. And yes, if advertising is working to generate demand, it will generate searches too so that share of search can tell you something about how your campaign landed.

But it doesn’t take into account the supply side of the purchase decision, and that’s a problem if you want to use it to say anything about whether a particular marketing investment is or was worth making.

A search for your brand indicates some willingness to purchase from you, but it doesn’t tell you how much people are willing to pay, or which product features they need. You can be an in-demand brand, with a high share of search, but if the price is wrong, that demand won’t convert to a sale.

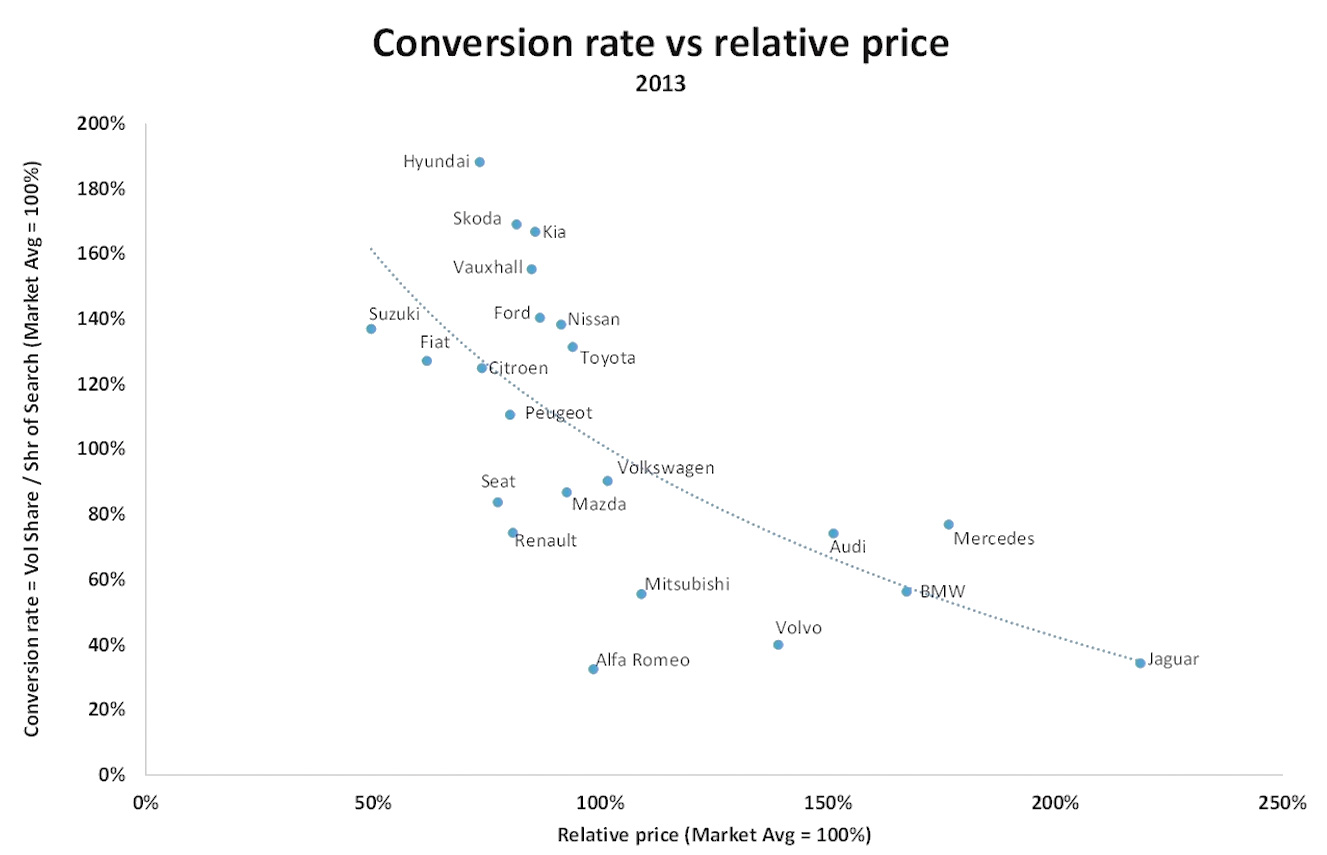

Les Binet does, of course, understand this. In his talk at Effweek in October, he introduced the chart below. It shows how, in his example category of cars, conversion from share of search to market share depends heavily on the price different brands charge.