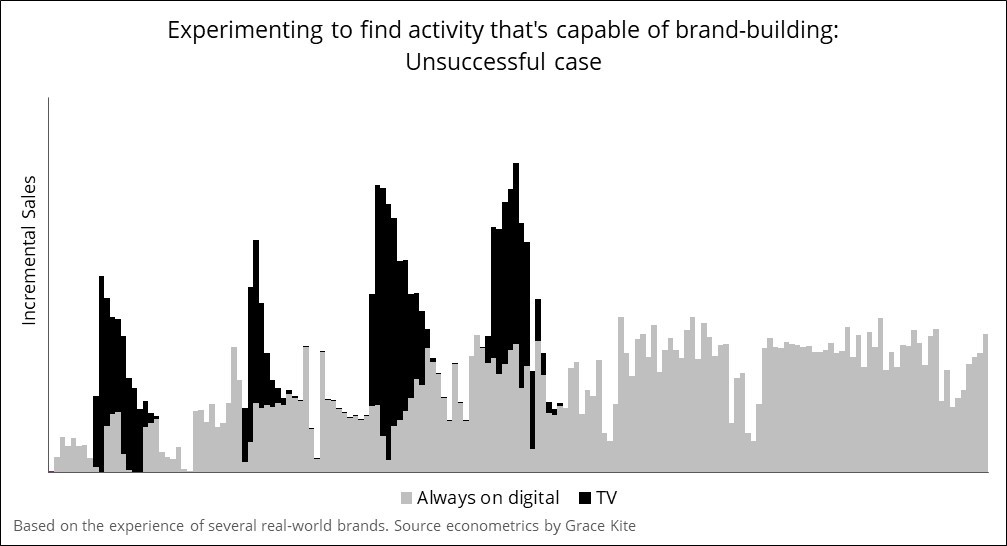

These examples don’t provide a model for successful advertising. They are never going to be immortalised in a stylised chart that has a viral life of its own. But they are important, not least because they are numerous. In our research, there were many more cases like these than trouble-free take offs into sustained growth.

It is an immensely frustrating situation for marketing directors and CMOs. Most that I talk to are very familiar with the long and short of it, but they find its recommendations hard to put into practice. Brand-building often requires large budgets, and, as we have seen, there is a very real risk that it’s an investment that won’t pay back.

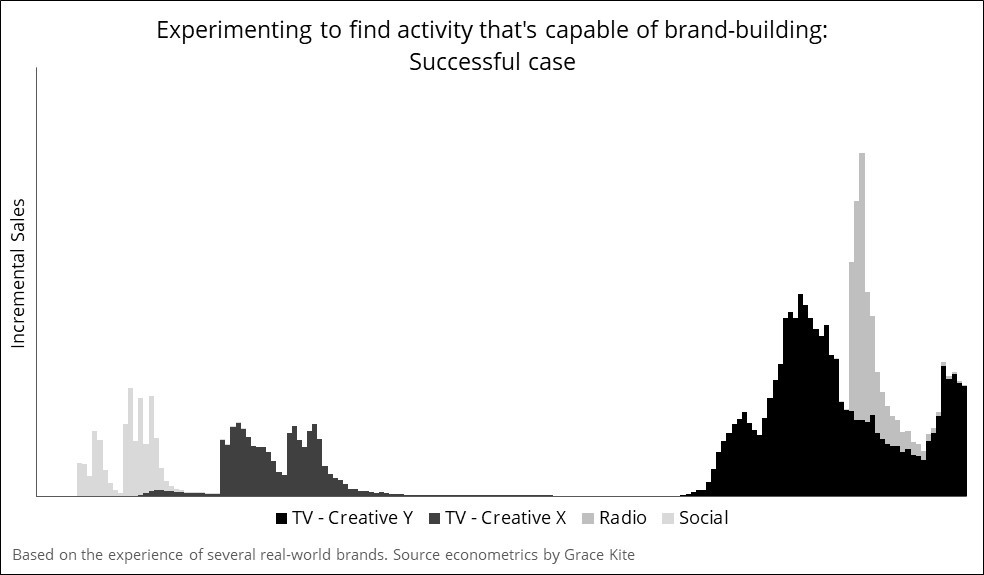

The uncertainty creates a catch 22. Businesses don’t know in advance whether their creative is good enough or whether they’re using the right media channels, and this makes it very difficult to commit the budgets needed to make a success of any creative/media channel combination.

Econometrics from a credible provider is the only evidence that can break the deadlock. Attribution is incapable of assessing long-lived effects and brand trackers are too far removed from the metrics the CFO really cares about.

Real world brands need to learn from failures as well as successes

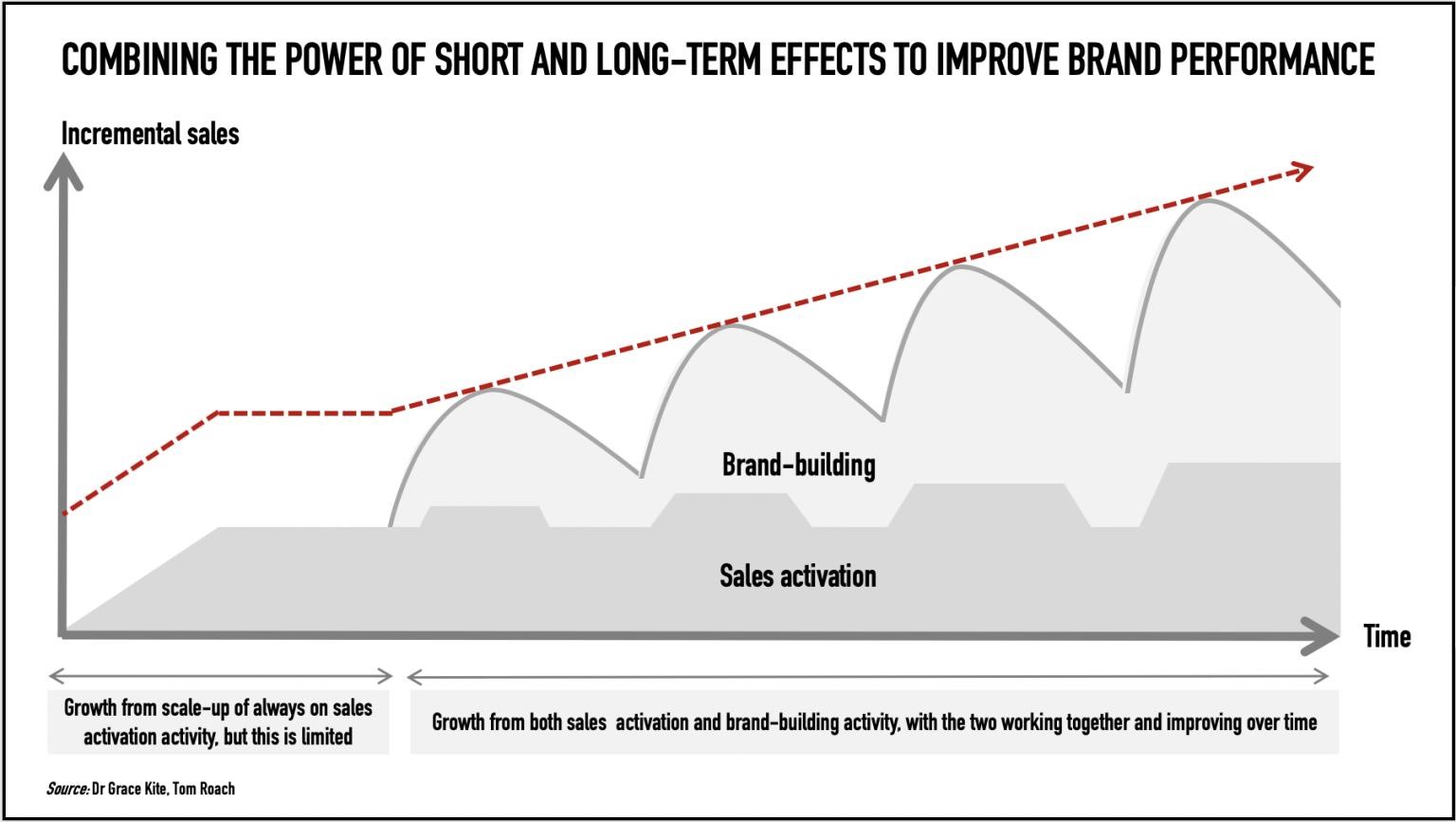

Together, the real-world examples outlined above tell a clear story. Communications can drive growth, and brand-building is the only way to sustain it over the long term, but it is hard.

As an industry, we should do more to help. So far, we are guilty of focussing on success stories and repeating narratives that are not easily attainable for many businesses. We don’t celebrate the long and often frustrating work that advertisers and their research partners carry out in search of the right blend, but perhaps we should.

Even more importantly, we should do a better job of drawing out the lessons from this work. Commissioning a great creative and putting a lot of money behind it may be a route for growth, but as a piece of advice its not helpful. CMOs need to know how, and importantly they need to know how to make the whole thing a lot less risky.

In the real world, that’s where success comes from.

Without believable research, the outcome is typically inaction. Brand-building plans just don’t make it past the CMO’s boardroom pitch for the money.