Three years ago, I hired one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. She’s just really clever. And not in that baffling ivory tower way, in a really human way. She used to value derivatives in the city and even though that’s very complicated, in the interview she explained it in a way I immediately understood.

Since then, she’s learnt market mix modelling and all about effectiveness faster than I thought was possible. She makes it look like a walk in the park. She’s gone from zero experience to director since that interview, all the while offering wise and trusted advice to our clients and team.

If the terminology used to describe marketing payback is confusing to an amazing lady like her, there must be something genuinely wrong with it. And it’s true, in our conversations, it became clear to both of us that while some key concepts are fine, others are flat out wrongly labelled.

“Return on investment” is fuzzy, but workable

Advertising ROI gets a lot of stick. Prof Ambler from London Business School wants to bury it, Les Binet says using it unwisely will destroy your brand, and even Andrew Willshire, one of very few outspoken econometricians, says it stinks.

But love it or hate it, we can’t live without it. Anyone that regularly talks to CMOs and CFOs knows it. What you get back from what you spend on advertising is something businesses need to know. There’s no going back to the old days when ads didn’t need to pay for themselves and gut feel was enough to secure budgets.

There is, of course, ambiguity around ROI. We’re often not as precise about what it really means as we could be. We don’t surround ROI with enough clarifying words.

For example, an objection in Prof Ambler’s piece that’s very relevant in these times of high inflation is that ROI doesn’t take into account the effect advertising has on willingness to pay more.

He’s right, this is an important effect of advertising. Market mix modelling confirms it – good advertising aired consistently often makes it possible to charge and maintain a higher price. And the benefit is substantial. McKinsey looked at S&P 1500 companies and estimated that on average a 1% higher price would bring around 8% more profit.

To be precise about this omission we should add “conservative estimate of” before we say ROI. And we could also be concrete about the time period, “long term” and “short term” mean different things to different people, or swap “investment” out for “adspend” if the effect is short-lived.

These things would help, but they were never something that confused my smart newcomer. Perhaps she’s only been at the right kind of market mix modelling shop, but in her experience these details were mostly clear at the point of decision-making.

“Cost per acquisition” is badly misleading

The same isn’t true for that other payback measure – cost per acquisition/CPA.

When marketers see “cost per acquisition” in google analytics or other platforms, many believe it is what it says it is: the cost of acquiring a new customer by spending advertising money on the platform.

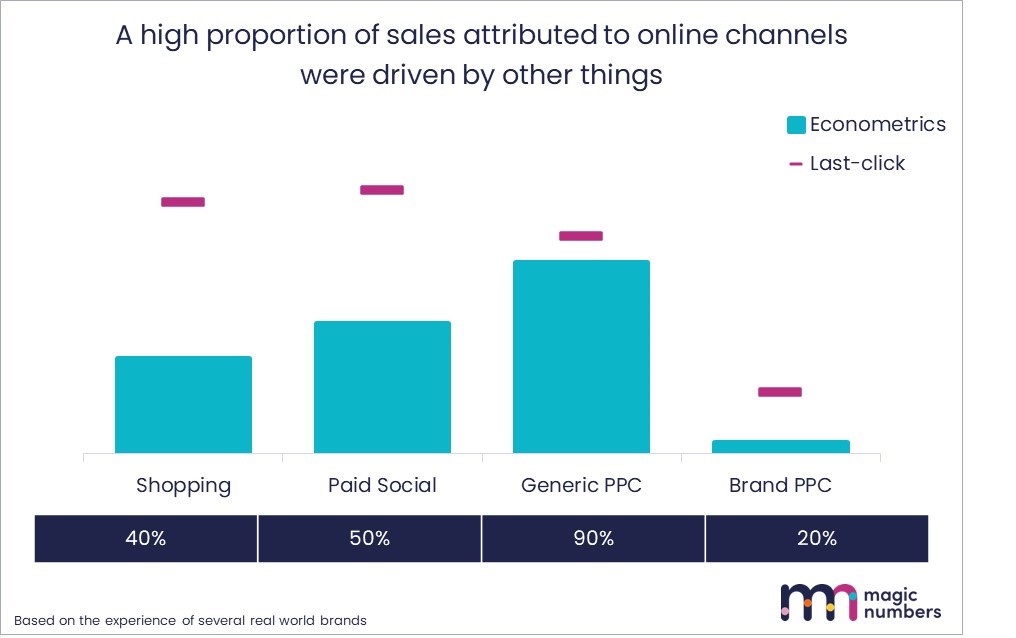

It is, in fact, nothing of the sort. The dashboards present everyone who clicked on an ad and then went on to buy something as if the sale was caused by that ad. But a large proportion of people who click on online ads were already on their way to buy. Their choice was prompted by an offline ad, a deal, the weather, or the economy.

This means that “cost per acquisition” is not just a bad label. At best it’s a grave misunderstanding. More likely it’s a flat out lie, told because it benefits the platforms that report it.

And the implications are both bad and big. Businesses who believe CPA is what its label suggests massively over-allocate money to ads that preach to the already-converted.

And it’s a mistake that’s hard to reverse. It’s not unusual to meet online-first organisations who can’t stop doing brand PPC even when they’re always at the top of the organic listings. When you ask why, it turns out the board is used to seeing that low CPA and don’t have time to learn why it’s not right.

“Incrementality” is just weird

So, what can marketers who understand the problems with CPA do? Well, absent a benevolent dictator re-writing the dictionary, the innovation has been to invent “incrementality”, “incremental sales” and “cost per incremental acquisition”.

“If a sale caused by an ad is incremental”, I explained to my clever friend, “it means it’s a sale that wouldn’t have happened without that ad. That wasn’t going to happen anyway”. She raised an eyebrow. “So, if it isn’t incremental, how is it in any sense caused by the ad?” she asked.

And she’s right, to a newcomer in marketing effectiveness “incrementality” is a very weird concept.

But we do, as an industry, need it. Until the day comes that all marketers – even those that have grown up in the Google and Facebook era – understand the truth of CPA, we will need to distinguish all-sales-that-follow-a-click from sales-caused-by-the-clicks.